On the outskirts of the Mexican resort town of Tulum, overlooking the Caribbean sea from a densely jungled hilltop, are the remains of a Mayan city known as Zama, or “Dawn.” The ruins look similar to other Mayan structures found across the Yucatán Peninsula, with their sharp angles and mystical engravings. That is, except for the walls, which—miraculously—still bear hints of the red paint with which they were originally coated.

Nowadays, we often imagine ancient Mesoamerican art and architecture as colorless, because most of them currently are. But just as with Greek and Roman statues, these artifacts were once aglow with bright colors. And not just any bright colors, but carefully chosen palettes and combinations that reflected the social, cultural, and spiritual beliefs of their creators.

Masked Male Figure with Dance Staff, Mexico, Campeche, Jaina Island, Maya, 700–900 CE, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Gift of John Gilbert Bourne. Photo: Museum Associates/LACMA.

Uncovering those beliefs is the main objective of “We Live in Painting: The Nature of Color in Mesoamerican Art,” a new exhibition at the Resnick Pavilion of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art in California. Open until September 1, 2025, the exhibition presents a melting pot of mediums, cultures, and time-periods, from portrait paintings and excavated mural fragments to effigies, codices, and original work from contemporary Mesoamerican artists, produced with the same techniques and materials as their forebears.

One of the exhibition’s oldest—and most impressive—items is a group of clay figurines from Tlatilco, a pre-Columbian village in the Valley of Mexico near the modern-day town of the same name. The figurines, humanoid in shape, are thought to have been made between 1,200 and 900 BCD, coinciding with Tlatlico’s heyday. Like the walls of ancient Zama, these yellow-brown statuettes were originally painted a bright red.

Funerary Urn, Mexico, Oaxaca (Mixtec), 300–600 CE, Ceramic with pigment, Height: 13 3⁄8 in. (34 cm); width: 6 3⁄4 in. (17 cm); diameter: 6 1⁄4 in. (16 cm), Museo de las Culturas de Oaxaca. Photo courtesy of Museo de las Culturas de Oaxaca/ Ex Convento de Santo Domingo Guzmán.

Diana Magaloni, a conservation center director at the LACMA and lead curator of “We Live in Painting,” has done extensive research on the role of color in Mesoamerican art. “Some workshops and their artists developed a broad palette of colors to adorn their vessels,” she wrote in a 2021 paper. “Others prized line over color, painting whiplash strokes to render evocative if colorless tableaux.”

Others still, she continued, “used bichromy, manipulating a single paint in variable concentrations to create remarkable depth and movement over a static base.”

One of the first things visitors to “We Live in Painting” learn is that, for ancient Mesoamerican artists, picking the right color was about more than just aesthetics. The artists generally divided colors into five categories—black, red, blue-green, yellow, and white—and each was associated with unique concepts. As shown in the exhibition, blue-green and yellow represented the circle of life, and were used to paint things like water, breath, and sunlight.

Bowl, Mexico, Basin of Mexico, Teotihuacan, (Teotihuacan), 200–650 CE, Ceramic, Height: 3 1⁄4 in. (8.2 cm); diameter: 8 1⁄2 in. (21.7 cm), Museo Nacional de Antropología, México (Inv. 10-80616). Photo: Digital Archive of the Collections of the Museo Nacional de Antropología, México / INAH-CANON.

As explained in the exhibition catalogue, color in Mesoamerican art wasn’t merely used to represent subjects and concepts, but treated as a physical embodiment of those subjects and concepts: “A painting of a deity is that deity. A sculpture of a ruler is that ruler. By transforming the natural world into images, Mesoamerican artists deployed a creative power much like that of the primordial creator deities who crafted the cosmos itself.”

“We Live in Painting” also explores the materiality of Mesoamerican art. Without access to synthetic paints, artists from this part of the world—like their pre-modern European counterparts—created pigment from materials available in their immediate environment, including minerals, flowers, insects, and tree barks.

Mural Fragment of Scalloped Shell with Hands and Animal Head (detail), 350–450 CE, Teotihuacan, Lime plaster with pigment, 16 1/2 x 42 7/8 in. (42 x 109 cm), Museo de Murales Teotihuacanos, Beatríz de la Fuente. Photo: Museum Associates/LACMA, by Javier Hinojosa.

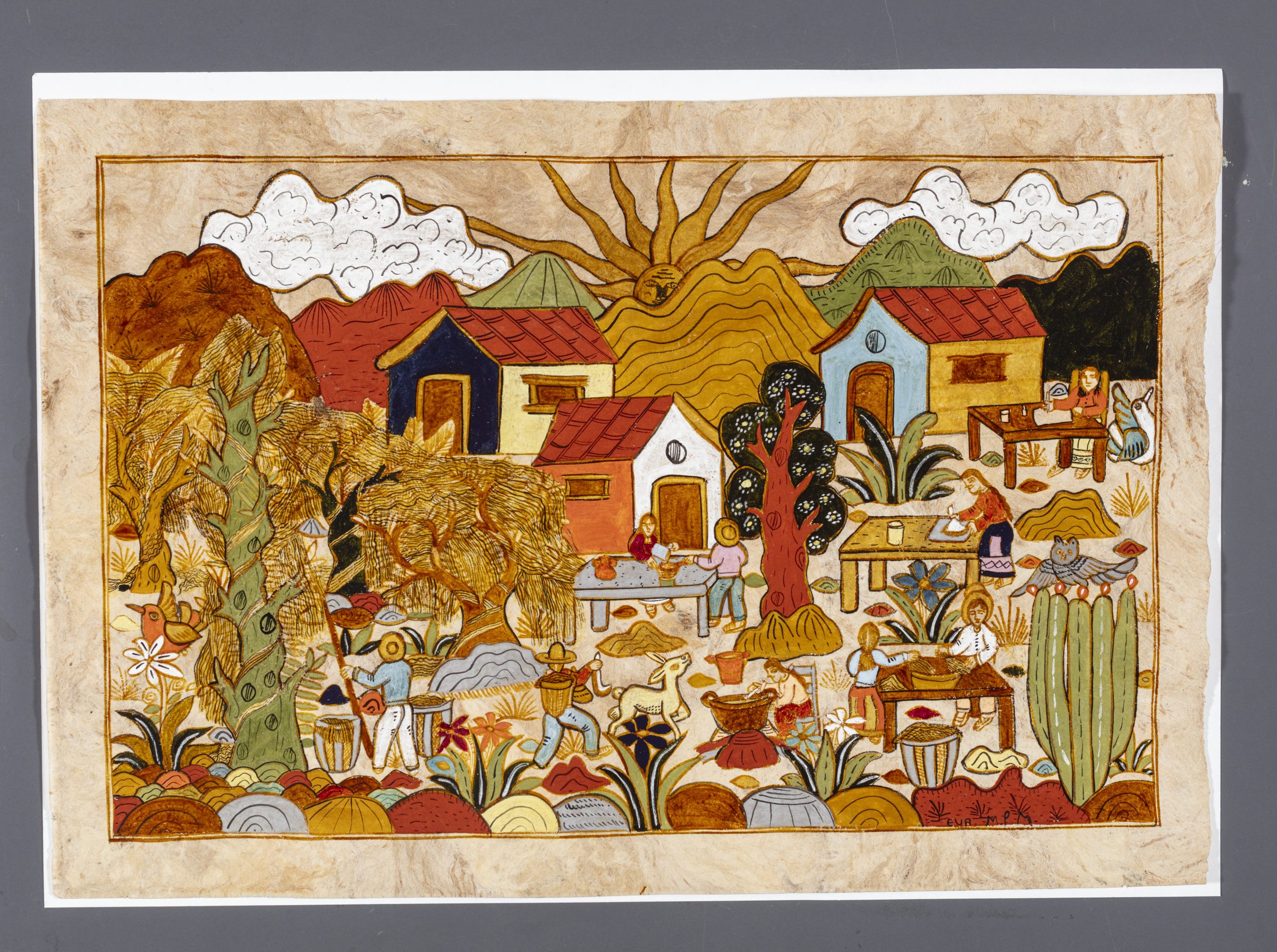

Last but not least, the exhibition features work from contemporary African American artists associated with workshops in Xalitla, Mexico, where artist and scholar Tatiana Falcón teaches community members how to produce pigment the traditional way. First among these contemporary artists is Porfirio Gutierrez, a California-based Zapotec-American textile artist who uses only traditional natural dyes.

“We Live in Painting” presents Mesoamerican methods for natural pigment-making as a viable, meaningful alternative to their modern, scientific counterparts. The exhibition, Magaloni says in a press release, “considers two sciences in dialogue: the Western science undertaken by contemporary scholars, and the Indigenous science of artistic production that, through millennia of empirical practice, engineered artificial pigments from the natural world. Progress in the former cultivates an appreciation for the latter, rendering the exceptional technical achievements of Mesoamerican artists legible to our audiences—a remarkable example of the collision between art and science.”