I texted a friend about an upcoming collection of Amazon reviews by the writer Kevin Killian. He texted back that he thinks a lot about all the great writing that has disappeared over the years—from early Usenet, billboards, MySpace, and weblogs—into the ether. We’re the same age, part of a generation who worries about writing lost on the internet as if it’s a phenomenon specific to digital media. We talk about the ephemerality of digital storage as if physical paper and papyrus were indestructible. But that is not true. We, famously, only have incomplete sections—data fragments—of the Greek poet Sappho’s work, for example. Anne Carson, in her translation, If Not, Winter, dealt with the problem by representing missing words with square brackets and empty boxes, used as place markers for what has been lost. In programming languages, brackets are important syntactic constructs and perform a similar function, holding-places within data structures, highlighting specific elements and helping navigate the code. Programmers have their own vocabulary around broken code and lost bits of information: bit rot, code rot, software erosion, decay, entropy, degradation, deterioration, or loss; whitespace, empty line, code gap, code deletion, merge conflict resolution issues, and corruption. Maybe one day, archeologists will mine servers, and future dig sites will be set up in digital spaces rather than geographic locations. Maybe they already do.

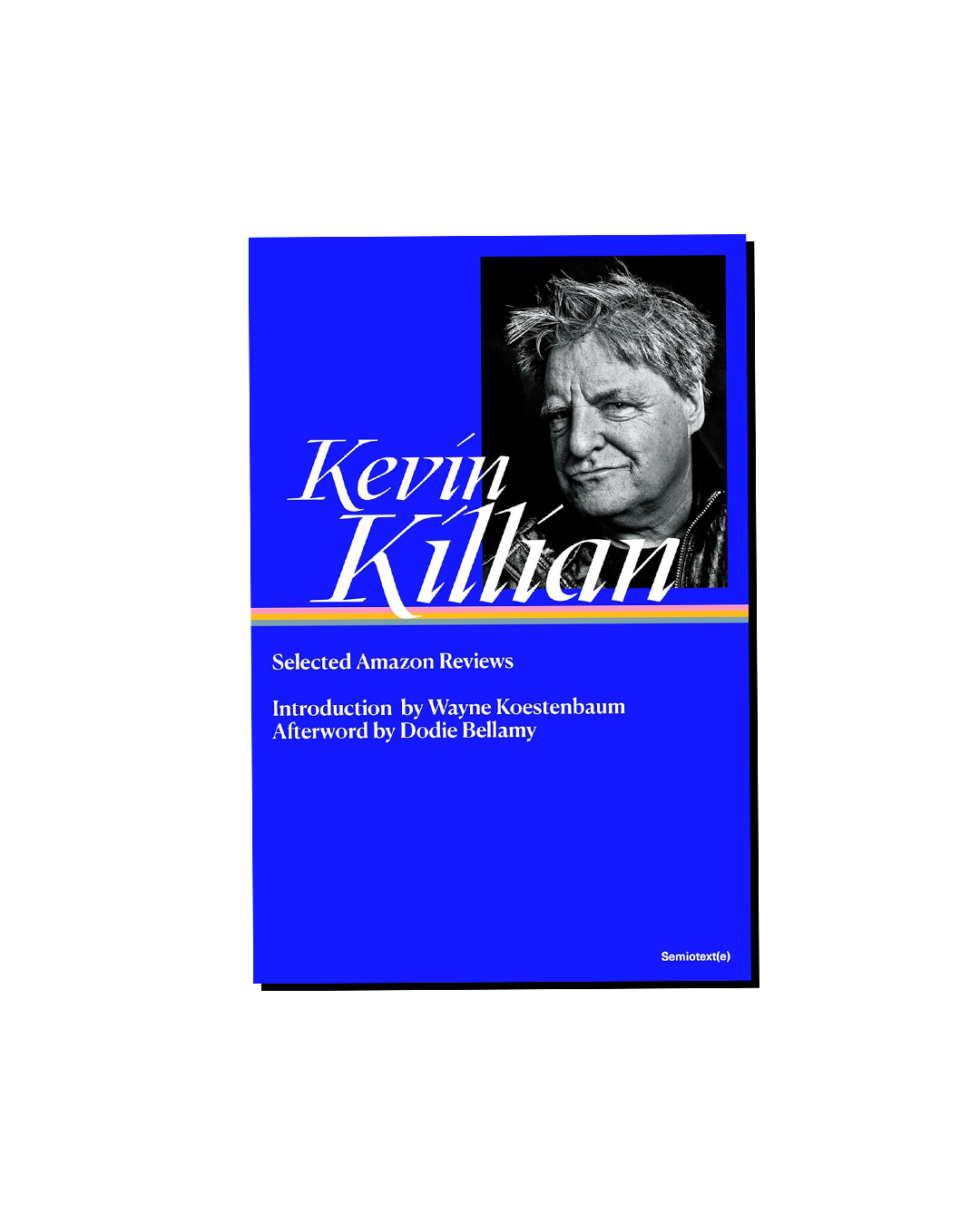

In 2021, writer Will Hall began scraping Kevin Killian’s reviews from Amazon’s servers and, thanks largely to his efforts, Semiotext(e) published Kevin Killian: Selected Amazon Reviews in November. The 697-page collection rescues from obscurity some of the over two thousand reviews the poet, playwright, novelist, biographer, editor, critic, and artist posted to the platform from 2003 until his death in 2019. He was a great consumer of books, music, and film but also discussed the odd product. Killian’s reviews can be read as meditations on the objects and media that populated our lives for the first twenty-five years of the twenty-first century. He imbued ordinary items – duct tape, a toaster, a DVD—with personal meaning. For example, when he wrote about Officemate Breast Cancer Awareness Pushpins in 2008, he focused on how the color changed with the light:

No two pushpins have the same exact tint of pink. And their colors change depending on the light. At morning, spill out the jar of Officemate Pushpins across your blotter in the morning sunlight. You’ll see a soothing, almost angelic pink on their tips, as friendly as a dog’s tongue licking your face.

He took the time to break down the pros and cons of the Multiple Orgasm Set II by NARS Cosmetics (blush, bronzer, and shimmer) in 2006:

Now, what I would like specifically to comment on today is the fact that you get not only one, not two, but three products packaged together with this product, and I think the combination may be cutting into sales instead of vice versa. The famous Orgasm blush, the color of pale, demure, Staffordshire pottery, is sitting next to the florid bronze tanner, like two squares in the old game show of Hollywood Squares.

And in 2012, he wrote three substantial paragraphs about the culinary perfection that can be found in a German Potato Salad Can (15 oz., Pack of 12). Often, he’d open with something like “as an American boy growing up in rural France.” Killian grew up on Long Island, New York. He didn’t take himself (or much else) too seriously.

I haven’t read any of Killian’s other work. The Amazon reviews are my first foray. He is a writer with a passionate following who—Cleveland Review of Books readers notwithstanding—is not as well known as he probably deserves to be. He is closely associated with San Francisco’s literary scene, living there for more than forty years, and, as a queer author, remains an important figure in that city’s LGBTQ community, even after his death. However, San Francisco’s literary culture, while strong and vibrant, is in many ways a closed system. Few of its authors break out or win national awards.

He was also a member of the New Narrative Movement, founded in the 1970s by novelists Bruce Boone and Robert Glück, two of Killian’s friends. A precursor to autofiction and a not-so-distant cousin to New Journalism, the goal of New Narrative writing is authenticity. Writers acknowledge the subjectivity of, and the author’s active presence in, the text. They embrace their voice. They include metatextual and pop-culture references, engage in identity politics and gossip, explore gender fluidity, write openly about sex, and apply techniques traditionally used in poetry (such as lyrical language, rhythmic line breaks, and unusual punctuation). It seems to be a movement committed to literary specificity in terms of accurately representing time, place, and individuals. Given all this, Amazon reviews are a near-perfect vehicle for New Narrative’s tenets.

Over the years, Killian told three different versions of how he started writing on Amazon, and his widow, the writer Dodie Bellamy, provides a fourth in a thoughtful afterward to Selected Amazon Reviews. All agree on the following points. In 2003, Killian suffered from a heart attack. Afterward, due to the trauma and medications, he lost his desire and ability to write. As his body chemistry adjusted, however, the urge returned, though he recognized the need to ease himself back into the work. He started posting short reviews on Amazon, typically a few sentences or a paragraph in length. These quickly grew into short essays. Killian typed fast, directly into the site, never stopping to edit. The original posts, according to Bellamy, were rife with typos. Even when he returned to composing the “theoretical-critical essays I used to write before my collapse,” he continued writing the reviews for the remaining thirteen years of his life. The final review, in the present selection, of the memoir Never Mind the Moon: My Time at the Royal Opera House by Jeremy Isaacs, is dated a month before he died.

Typical Amazon reviews lack a clear sentence subject. The author assumes (rightly so) that, given the context, a reader knows what they’re talking about. “Love the look, very cute and comfortable, and the glow in the dark is so fun!” Usually written in the first person, they nevertheless reveal little to no identifying information about their author. “Blended cream soup” writes Anne Baker in a three-word review of her new immersion blender. It is only from contextual signifiers that we see these users as parents, grandparents, spouses, siblings, or some misguided person who thinks a Pendleton wool blanket is the perfect wedding gift. Read through enough reviews of a product, and a piece of information will float to the surface: the most common use of a wheeled plastic bucket/container with a latching lid is for holding dog food. In 2023, Amazon reported that one hundred million customers submitted one or more product reviews to the site. The content of most is dross, median.

Likewise, Killian camouflaged his reviews in the cadence of the Amazon everyman. He embraced all the stylistic quirks, choppy sentence fragments and run-ons, either darting from point to point like a distracted squirrel or leaning heavily into declarative statements. His voice is overly casual, conversational. In one review, he forgets a person’s name, talks around it, and tells us, “I know, I’ll Google her name—oh, here you go, Sam Taylor-Wood, the one who’s directing Fifty Shades of Grey.” He seems to like closing with an odd, noncommittal, open-ended flourish. “Don’t let people tell you differently,” (The Midnight by Susan Howe), he writes, “Hmmm, threatened much, Virginia Woolf?” (The Life and Art of Elinor Wylie by Judith Farr) “And who received them?” “Her children, I guess,” (Letters to Jackie: Condolences from a Grieving Nation by Ellen Fitzpatrick).

Despite this, his writing is filled with the authorial specificity that the typical Amazon review lacks. He provides extraneous information, which, while not entirely inappropriate, runs on a parallel track to the information Amazon consumers seek. He also writes openly, even crudely, about sexual content, something you rarely see, even in reviews of erotica.

His knowledge of literature and film was encyclopedic and revelatory. Many of his film reviews function as obituaries for an actor or actress who recently died, sometimes posted on the day it occurred. Where we expect a review of the film Psycho, we find a tribute to the late actress Janet Leigh. Richard Donner’s Superman inspires a touching memorial of actor Christoper Reeve, posted the day after his death. Often, Killian goes rogue. In the space reserved for a review of 1979’s Kramer vs. Kramer, he laments of the young actor who played Justin Kramer’s never receiving a Juvenile Oscar for his performance (the last of its kind being awarded in 1961 to Hayley Mills).

His taste in literature was even more expansive and free-ranging than film. On April 6, 2007, he reviewed Tiger Traits: 9 Success Secrets You Can Discover from Tiger Woods to Be a Business Champion by Nate Booth. “Booth is an exciting and spirited writer,” he writes, “I would love to see him do a full-scale infomercial that would help us put the story of Tiger in perspective.” Six days later, he wrote about Divagations, an experimental collection that blends prose poems and essays by the French writer Stephane Mallarme. What starts as honest, low-brow cultural criticism inevitably belies a thoughtful beat. Discussing Averno by Louise Gluck, for example, he points out: “She must get tired of Anne Carson continually eclipsing her reputation with classical coverage all her own, with even more quirks than Gluck.” And about the biographer of Elia Kazan, he tells us, “Schickel is in love with the sound of his voice, and somewhere in the shredded coleslaw of his prose, a decent book lies unavailable to us, about the real Elia Kazan.”

How many shoppers scrolling for Prime Day deals recognized a mind at work? Killian treated Amazon like a notebook—filling it with information and insights that could easily have been built into longer, more polished pieces for the many outlets that published and actually paid for his criticism.

Selected Amazon Reviews rewards readers who dip in and out over days, weeks, and months, much like a book of poetry. Killian was a humanist of a sort, re-centering the individual experience on a site premised on selling to the collective. He manages to embed an impressive amount of personal information in unexpected places, leaving the reader to wonder what is real and what is imaginary. Moreover, and often in the same piece, the writing can move from very funny to strangely poignant. One of my favorites, his review of MacKenzie Smelling Salts, begins with a tragically tongue-in-cheek anecdote about his Irish grandfather:

My Irish grandfather used to keep a bottle of MacKenzie’s smelling salts next to his desk. He was the principal at Bushwick High School (in Brooklyn, NY) in the 1930s and 1940s, before it became a dangerous place to live in, and way before Bushwick regained its current state of desirable area for new gentrification. And he kept one at home as well, in case of a sudden shock. At school, he would press the saturated cotton under the nostrils of poor girls who realized they were pregnant in health class, before he expelled them.

He ends with his own reasons for using smelling salts, citing wildly diverging examples: his grief upon learning of the death of Paul Walker from the Fast & Furious film franchise abuts Killian’s disappointment at not being selected for the 2014 Whitney Biennial. Apparently, both were deeply traumatic experiences for Kevin. He also manages to fit, in passing, a reference to his ongoing heart problems:

Nowadays, with my ongoing heart problems, I use them only when I’m in a deep grief or have had a shock. I was so sad when Paul Walker died. And then again one day I came staggering down the stairs, having been passed over for inclusion in the 2014 Whitney Biennial by a troika of careless curators, I simply collapsed out of grief, and it took my wife a minute or two to locate the MacKenzie’s, but passing it under my nose, as though she were my grandfather ministering to the pregnant girls of yore, or the sore-bottomed “tough guys;” and suddenly I snorted and came awake, shot to my feet, still grieving for my disappointment but at least able to function and go back to making my art, feeding the cats, etc., being a man. In time of deep mourning thank goodness for small miracles!

Over the years, a few of these reviews were collected in chapbooks, including the one quoted above. I wonder if Killian was surprised by how much attention his Amazon reviews received. After discovering his hobby, other writers began clicking the “Helpful” button to show their support, pushing his reviews to the top of the feed. Unfortunately, the editors of this volume did not preserve the Helpful/Not Helpful ratings, only the stars. Ending each review with “42 people found this helpful” adds a rhythmic repetition reminiscent of the work of the Oulipian writer Georges Perec, who I’m sure would have loved Killian. As Bellamy writes in her introduction, Kevin “rejoiced in the Not-Helpful ratings” even more, performing “a burlesque of torment” in public.

It was this attention, however, which pushed what allegedly began as writing exercises into a dedicated “poetry” project, by his own admission. I get the sense that calling it a poetry project was Killian’s way of reckoning with the reality that his writing was being absorbed and made a part of the Amazon machine. The reviews were essentially and unromantically unpaid labor in the form of user-generated content, as he acknowledged in an interview with Jon Fran. You can still read some on the Amazon site, but most are now gone.

No one wants to be forgotten. I do not think it’s a coincidence Killian started writing the reviews after his heart attack. Why did he keep going? Most likely, it was because he enjoyed the writing and got something out of it—pleasure, practice, and a bit of notoriety. But mainly, I think the project grew out of habit and compulsion. In a similar way, the graffiti art of Keith Haring, Jean-Paul Basquiat, and Banksy began in subway tunnels, one tag and mural at a time, until it grew into bodies of work collected and coveted by museums worldwide. In Killian’s case, the global commerce platform was his ugly brick wall, his subway platform, and his train car. Coming away, I like to imagine him gleefully typing, manipulating the Amazon review forums into something that had little to do with the consumerism they had been created to support: Killian tagging a digital wall to remind everyone KEVIN WAS HERE.