“I can take any space and call it a bare stage,” Peter Brook wrote in his seminal treatise “The Empty Space.” “A man walks across this empty space whilst someone else is watching him, and this is all that is needed for an act of theatre to be engaged.”

Actor and spectator were for Brook the building blocks of this art form. American avant-gardist Richard Foreman, who died Jan. 4 at age 87, took Brook’s proposition a step further, envisioning a theater that didn’t even require the presence of a performer.

“To make theater, all you need is a defined space and things that enter and leave that space,” he wrote in “Unbalancing Acts: Foundations for a Theater.” “You could even make a play without an actor. A jar could be thrown out into an empty space, and a minute later a stick from offstage could push that jar one inch forward. That would function as theater.”

Foreman’s idea of theater, born in opposition to the mainstream, was an acquired taste that some of the most rigorously inventive sensibilities couldn’t get enough of. Along with the Wooster Group, Robert Wilson and Mabou Mines, Foreman extended the radical traditions of the Living Theater and the 1960s collectives that followed. He became one of the pillars of New York’s downtown theater scene, an elder statesman in the 1990s and 2000s who remained miles ahead of those younger innovators galvanized by his example.

“Theater in the past has used language to build: What follows what?” he wrote in an early manifesto. He set out to destroy the logical underpinnings of the art form by transforming drama into a carnivalesque collage that discovered surprise not through suspense but through stasis. The company he founded was called the Ontological-Hysteric Theater, and the name tells you nearly everything you need to know about a theatrical trailblazer who found manic inspiration in the metaphysics of being.

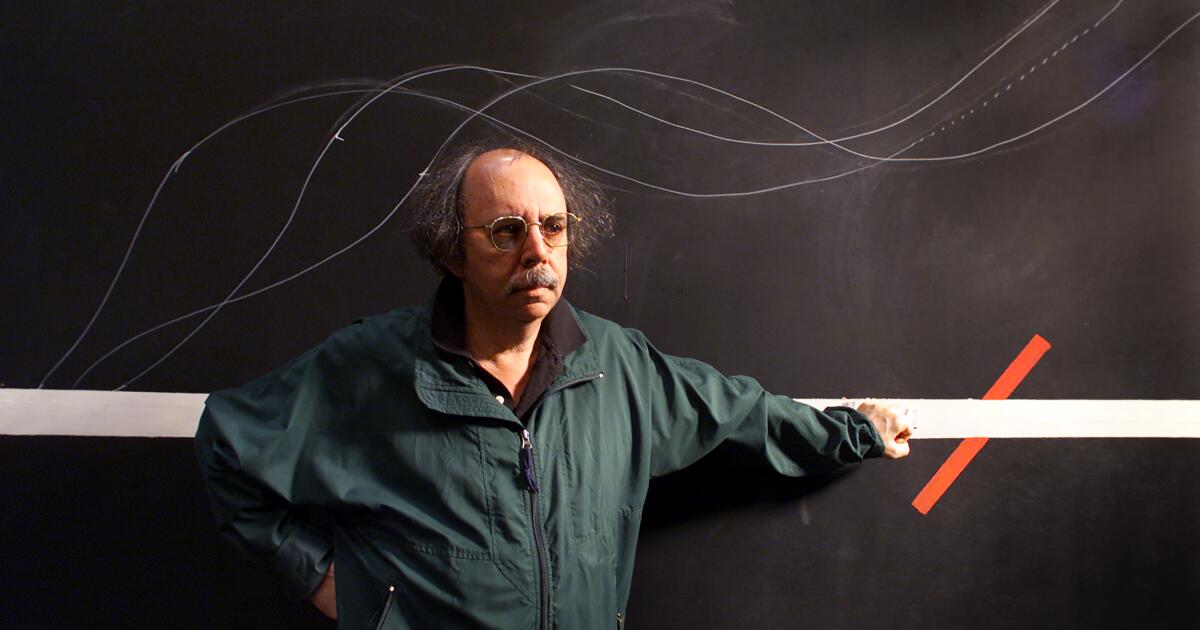

Richard Foreman, lower right, with composer Michael Gordon, working on the theatrical opera “What to Wear” in 2006, reflected in the mirror held by members of the ensemble.

(Lawrence K. Ho / Los Angeles Times)

In his book “American Avant-Garde Theatre: A History,” Arnold Aronson categories Foreman and Wilson as “post-Einsteinian” artists confronting a universe “of uncertainty principles and chaos theory.” Their work, he writes, “challenged post-Renaissance (i.e. modern) understandings of time and space within theater; it disrupted the act of viewing by slowing down action to almost imperceptible movement, extending the length of performance beyond normal limits of concentration, and fragmenting both the viewing frame and the arc of the production, thereby forcing the spectators to re-examine their own notions of performance and their own perceptual process.”

Foreman’s biography doesn’t suggest a revolutionary path. He grew up in the affluent New York suburb of Scarsdale, where he discovered his passion for theater in high school. He was educated at Brown University and the Yale School of Drama, where he received his MFA in playwriting. His credentials could have gained him immediate entry into the establishment elite, but he had no interest in perpetrating what he took to be an obvious fraud.

Foreman diagnosed the “resistance” to his work as a resistance to his existential worldview. “My work has always been very aggressive in maintaining that life as we know it (and as normal theater knows it and presents it) is an absolutely silly, childish (and understandable) avoidance of the emptiness at its center,” he wrote in “Ages of the Avant-Garde.”

What frustrated theatergoers most about his work, however, was that it forced them to stay in the theatrical moment. Yielding attention can be painfully difficult. Myriad are the ways we seek to paraphrase art into digestible meaning. The impulse to domesticate performance into a comprehensible story was denied by the sensory bombardment of his productions.

In her epochal essay “Against Interpretation,” Susan Sontag concluded with a memorable flourish: “In place of a hermeneutics we need an erotics of art.” Foreman theater answered this call by creating dreamscapes that eluded our intellect’s mania for control.

“How can I frustrate the spectator’s expectations, including his tendency to identify with the performance of a powerful actor?” he asked in “Foundations for a Theater.” “How can I frustrate the flow of the action within the play and prevent the inevitable drift into normal, narrative form. How can I frustrate the commonplace drive toward narrative understanding in the spectator that awakens in his consciousness a habitual identification with the goals, values, and mind-sets received from our social and cultural system?”

The point of all this frustration was to make us more mindful of our perceptual shackles. “To frustrate habit is to uncover ways our impulses might be freed for use in more inventive behavior,” he wrote.

Attending a Foreman production at the St. Mark’s Theater in the East Village was a contradictory experience. On the one hand, you knew you were going to be physically captive for an unbroken 70 or so minutes that could feel like a never-ending marathon. On the other hand, your mind was free to make what you will of the strange sights and sounds overloading your consciousness. Unlike technology companies that work to ensnare (and monetize) our attention, Foreman entrapped our bodies only to liberate our minds. He shared his dreams to provoke our own.

Foreman was a prolific playwright, but I consider him more of an auteur than a dramatist. He won acclaim for his audacious productions of classics (“Threepenny Opera,” “Don Juan”) and could draw out the dynamism of new work by other writers, as he did in Suzan-Lori Parks’ “Venus.” But it was in the staging of his own plays that he approached the Wagnerian ideal of the Gesamtkunstwerk or integrated artwork.

Yet he wasn’t tyrannical about the afterlife of these dramatic curios. In a note to “Bad Boy Nietzsche! and Other Plays,” he writes, “I suggest that each director re-conceive these texts and create a staging that elaborates on his or her own private vision of whatever world these texts seem to suggest.” Samuel Beckett, a stickler for faithfulness, didn’t share this laissez-faire attitude toward his stage directions, which he expected to be punctiliously observed by others.

When the Wooster Group came to REDCAT last fall with a new production of “Symphony of Rats,” it was clear that Foreman’s play was being filtered through the Wooster Group’s distinct sensibility. These two giants of New York’s performance avant-garde have a good deal of history in common, but what distinguished Foreman’s work — and what I am so grateful to have experienced regularly in the 1990s and early 2000s — was the exploratory consciousness playfully probing the fun house of sentient existence.

Foreman suggested that theater could take place without performers, but his theatrical canvases deployed actors of unforgettable individuality. Their eccentricities helped define the mise-en-scène of his productions as much as any aspect of the design that Foreman meticulously presided over. David Patrick Kelly, Kate Manheim (his second wife), Henry Stram, Tony Torn, James Urbaniak and Juliana Frances Kelly, among numerous brilliant others, shaped Foreman’s work and were shaped by it, ensuring the legacy of an American original, whose cryptic, frisky like we shall not see again.