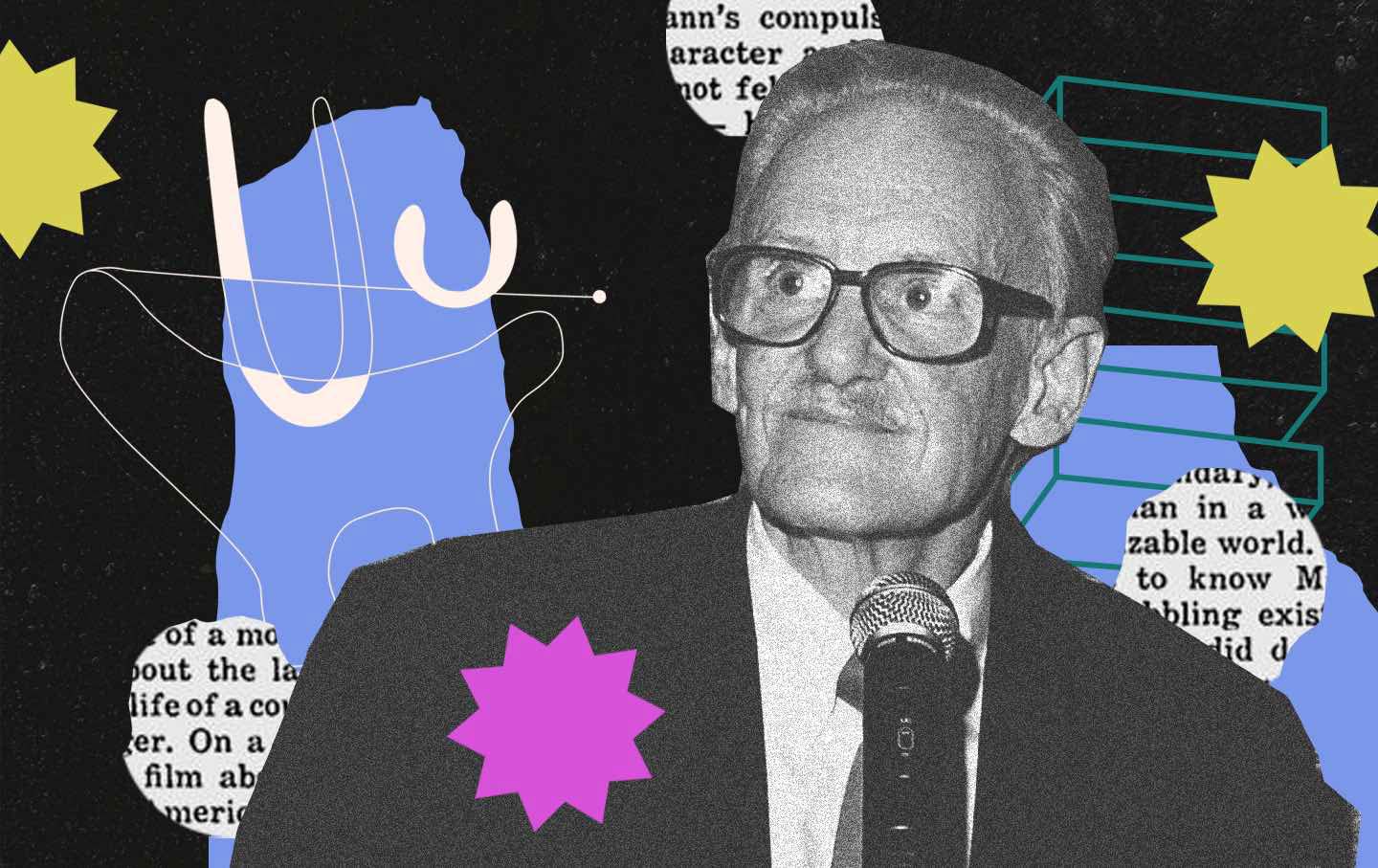

His art criticism fixated on the narcissism of the entire enterprise. But over six decades, his work proved that a critic could be an artist too.

It can be argued, with some important caveats and qualifications, that Peter Schjeldahl was the most inventive, entertaining, and self-observing art critic to have ever worked in the English language. For 60 years, give or take, he struck himself like a tuning fork against works of art and attempted to transcribe the way his nerves vibrated to the aesthetic. These transcriptions involved dense, epigrammatic sentences, zany metaphors, and a chatty authority that was both deceptively approachable and disarmingly smart. Although he put himself in the bloodline of poet-critics like Baudelaire and Frank O’Hara, their prose never approaches anything like the constant, look-at-me lexical wizardry of an exhibition review by Schjeldahl. His writing credo: “Concentrated. At least one idea per sentence. Melodious, I hope. With jokes.”

Books in review

The Art of Dying: Writings, 2019-2022

Buy this book

From his early pieces in ARTnews in the 1960s to his final review in The New Yorker in 2022, Schjeldahl’s career spanned from Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society and Andy Warhol’s golden years to Bidenomics and Beeple, with only one brief interruption in the mid-1970s—when he tried to quit art criticism and get back to poetry (his true love), but realized “there was nothing else that I did very well that they pay you for.” Having a career that lasts over half a century is not unusual, but being an art critic for that long definitely is. An art critic must endure (or enjoy) the constant grind of gallery-going and press junkets, an oppressively swampy environment of mega-wealth and self-congratulation, and the never-ending churn of the “new.” It’s also a job that easily corrupts, as Schjeldahl discovered—gallerists try to buy you, artists try to sleep with you—and like many writers, critics have a talent for alienating friends and family (as Schjeldahl did), falling prey to substance abuse and addiction (as Schjeldahl did), and seesawing between narcissism and self-loathing (as Schjeldahl did). He was also, to the dismay of his family, prone to breakfasts of bacon and Entenmann’s chocolate donuts, negligent in matters of dental hygiene, and a lifelong smoker—typically three packs a day.

Part of what made his 2019 essay “The Art of Dying” canonical on arrival—it begins with the indelible line “Lung cancer, rampant. No surprise”—was its unsentimental, warm-hearted clarity not just about death but also a life in criticism. A voice that many readers had known for years in The Village Voice, where he did three stints, and The New Yorker, where he’d been the art critic since 1998, was now trained directly on itself, with no artist or object to mediate it. Schjeldahl’s reviews were always an invitation to watch him wrestle with his own biases and hang-ups in the prosecution of his science—in fact, that was one of the pleasures of reading him: the feeling of transparency, even of complicity. His “I” was an instrument for nudging you closer to an artwork. Persuading you, for instance, to linger on a tiny oil painting of asparagus by Manet instead of the greatest hits: “I was feeling hostile toward masterpieces, which seemed to be ganging up to intimidate and exhaust me.” You wanted to hear this voice’s preferences and peccadillos, its hyperbolic riffs and weird commands. Forget all of those predigested “trumpeting masterpieces,” it said. Consider the asparagus.

Schjeldahl’s death was not just the death of a person but of a whole approach to writing about art. It was an approach that many people loved and that some people hated, because, on the surface, it seemed like he had turned art and language into one large epicurean buffet. Schjeldahl liked to sling around words like “ragamuffin” and “butterball” alongside “hierophant” and “retardataire.” Or to imagine, say, the taste in a photographer’s mouth (e.g., “cigar juice and microbial cultures spiked with adrenaline by-products”) before he even said a single word about the photographs.

Every Schjeldahlian skeptic always seems to be circling the same question: Is this art criticism? Or just art writing?

A new collection, The Art of Dying: Writings, 2019–2022, gathers the title essay along with everything Schjeldahl wrote after he was diagnosed with cancer. His “premature eulogy,” as the actor Steve Martin (and Schjeldahl’s friend) calls it, preceded 45 more essays in The New Yorker. I remember reading those pieces as they appeared in the magazine, month after month, and having the same uncouth thought: How is this man still alive? One day, he’s reading his own last rites, two feet in the grave; the next, he’s bopping around the Upper East Side and the Bowery. A number of the pieces were written during the pandemic, at the height of lockdown, and so belong to that strange blip in the history of exhibition reviewing when critics were housebound and had to invent occasions for reviews; or write about paintings from a distance, mediated by a screen; or pivot to book reviews, as Schjeldahl did. But he also made it out of his home to the Whitney Biennale, to MoMA and the Morgan, even to the Prado in Madrid to see his favorite painting (Velázquez’s Las Meninas). The secret to Schjeldahl’s second wind, in the end, was a successful course of immunotherapy. It gave him enough lifeblood for one final, miraculous sprint of writing.

Current Issue

Even as the art world rapidly changed during Schjeldahl’s life, with its parade of post-minimalist projects, its explosion into decadence in the 1980s, and its contractions after the 2008 financial crash, Schjeldahl’s voice in the new collection is almost indistinguishable from his writing in the 1970s, when his style took shape. His tastes became more varied over time, more alive to patterns of racial exclusion and gender prejudice in canon formation; he also became less paranoid about the competition, less prone to look over his shoulder at what other art critics were saying. In the end, he outlasted them all.

“The Art of Dying” was a major deviation. For a few weeks, between Schjeldahl’s cancer diagnosis and an electrical fire that burned down his Greenwich Village apartment in 2019, autobiographical fragments started tumbling onto the page. Suddenly, the prospect of death made writing seem like a breeze. He’d tried his hand at memoir in the 1980s with a Guggenheim grant but bought a tractor instead. This time, he ended up with a mini-masterpiece.

The only thing Schjeldahl wrote that really compares to “The Art of Dying” is a 1976 poem called “Dear Profession of Art Writing.” It’s a valedictory letter to the art world in which he announces his plan to quit criticism and get back to poetry: “For 12 years fount of my sustenance, social identity, claim to fame, / without you where would I be today?… you, Profession of Art Writing.” The poem is barbed and funny, pugnacious and self-debasing—sort of like it was written by a scorpion wearing a toupee. He calls Clement Greenberg “a worm-eaten colossus,” Harold Rosenberg a “honey-tongued blowhard,” and Jeremy Gilbert-Rolfe “totally crackers.” Then he turns the knife on himself. Peter Schjeldahl: He’s an intellectual “lightweight,” an approval-seeking jerk, a proud owner of a “starved and sneaky ego.” Criticism, he admits, was never just about a love of art or the need for a paycheck; it was about poetic glory: “But can only art be beautiful? / Can’t I be a little beautiful, too?”

The poem turned out, like “The Art of Dying,” to be a botched exit: Schjeldahl was back to writing criticism just a few years later.

For academic art historians and hard-nosed critics, Schjeldahl was many things—a skilled writer, a dilettante, a court jester, a “feeler”—but he simply wasn’t a critic. A real critic was a goad to the bourgeoisie. A real critic aspired to liberate the oppressed past, to invigorate future possibility. The belletristic critic, by contrast—the Peter Schjeldahls and Dave Hickeys—avoided rigorous engagement with art and history and feasted on their own reactions: writing ornate weather reports on mental climate and body temperature in the presence of an object. Instead of thinking against or toward an artwork, the belletrist created a stylish complement that functioned as a “critical placebo,” feeding cotton candy to readers and helping to sell magazines—whether the critic intended it or not.

The signal difference between Schjeldahl and the hard-nosers is that he doted on his audience. He saw himself as belonging to a generation of critics who didn’t think that “somebody should have to crawl over broken glass to get to art.” He wasn’t a popularizer, exactly—he balked at the idea that he was dumbing down art history for the general reader—but he nonetheless felt that his readers dictated the terms of his writing. The function of criticism, for him, wasn’t to prescribe or proscribe; it was to “connect.” To seduce and please, rather than épater la bourgeoisie. And so even when Schjeldahl was alive to the wreckage of capitalism, and willing to describe it, he wasn’t interested in taking up arms against it. “I’m the kind of liberal,” he wrote, “who is perhaps oversensitive to the feelings of all constituencies.” While criticism, for Baudelaire, was necessarily “partial, passionate, political,” for Schjeldahl, it was—above all—pleasurable. Art, he claimed, was “about 100 percent” pleasure.

This is where Schjeldahl sold himself short and played into the hands of his critics. Well, this and the academic-baiting—with his jabs about the “death embrace of academe,” or his description of obscure writing as “a form of territorial behavior that can be compared to the behavior of monkeys in close circumstances.” (You couldn’t exactly call Schjeldahl’s writing a paragon of clarity, either.) One can sense that Schjeldahl knew, deep down, that criticism was about more than transmitting the pleasures of art, and that art did, in fact, have a social value—that it wasn’t just a chocolate fountain of self-serving, autotelic pleasure. In “Mortality and the Old Masters,” a tender essay from 2020, Schjeldahl reflects on the capacity of art to “disrupt your life’s habitual ways and means,” to melt down the ego and transport you to a “past that seems to dispel, in a flash of undeniable reality, everything that you thought you knew.” That’s not a summons to revolt, but it’s more than just pleasure.

For Schjeldahl, the critic was a fallen, self-obsessed creature who made the most of their narcissism by revamping it as “basic operating equipment” for criticism. This was partially about enjoying the sound of your own thoughts, and learning to heed them, but it was also about being honest with yourself. According to Schjeldahl:

One of the deepest motivations of all critics is to try to make the world more comfortable for themselves. I think at the root of the critical impulse is some kind of adolescent outrage at growing up and discovering that the world is not nearly what you hoped or thought it might be. Criticism is then a career of trying to move the world over and make it more habitable for your own sensibility.

Now, for comparison, take this summa of the critic’s psychology from the art historian Hal Foster: “To be a good critic, you have to have a touch of ressentiment, as Nietzsche would say. Not personal envy, but social antagonism.”

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →

In both cases, there is adolescent spleen. But for Foster, the rewards of criticism flow outward. Even when criticism clarifies one’s relationship to oneself, it fundamentally has a social function—stimulating a community of readers to rethink their relationship to the present, to recover what has been buried or lost, to imagine utopian possibilities for the future. For Schjeldahl, on the other hand, criticism is a closed circuit that begins and ends with the critic. Whether the critic admits it or not, he’s really attempting to design a world that suits him.

If you read Schjeldahl’s account of his own parenting, or the memoir by his daughter, Ada Calhoun (Also a Poet: Frank O’Hara, My Father, and Me), it’s clear that the principles of Narcissistic Criticism extended beyond his writing to certain habits of living. By Schjeldahl’s own lights, he was an absentee parent and a “self-denigrating narcissist.” There’s nothing to dispute there. What I don’t buy is that narcissism defined his criticism. His defense of narcissism, his pleasure principle—they’re stale reactionary positions he cultivated to justify his talents, to insulate himself from the approval of others. If you’re repeatedly rewarded by editors and readers for writing stylish, self-reflexive pieces about art but simultaneously have every credentialed intellectual and self-serious art historian turning up their nose at you, it’s not surprising that you’d be defensive.

The serious critics wanted Schjeldahl’s audience and authority, and his gift for writing; Schjeldahl wanted their erudition and their blessing. The serious critics sneered at his jokiness; he smirked at their lack of humor. Clearly, they both got under each other’s skin. In his goodbye-art-world poem from 1976, Schjeldahl wrote: “Still, I have craved in vain the approval of my betters, / the ambitious toilers, the scholars, the committed…” At some point, he stopped craving in vain and embraced who he was (or thought he was): a wordsmith serving up inconsequential delights. He said that art was merely “a holiday of the spirit on the crowded calendar of life lived.” That it was time to accept “art’s limits as a force in the world.” Let’s be honest, he said. It’s only art.

What I love about this deflationary position is that Schjeldahl’s body of work—his art criticism—is one of the best counterexamples to it there is. It’s almost as if he were setting up the punch line himself. His use of language could make art more than art. It’s why so many people loved reading him. The day he died, it felt like a door had closed somewhere in the corridors of the English language. The world had seemed more vivid, more keenly perceived and interesting and worth understanding—and yes, even worth fighting for—with Schjeldahl as a guide. His prose really could do that. Or at least it did that for me.

More from The Nation

Oppenheimer’s latest film, The End, is a Golden Age, postapocalyptic musical crying out from the depths of the earth.

Peter Sellars

In Missing Persons, Clair Wills’s intimate story of institutionalized Irish women and children, shows how a family’s history and a nation’s history run in parallel.

Books & the Arts

/

Emily McBride

A talk with Dionne Brand about her recent book, Salvage, which looks at how the classic texts of Anglo-American fiction helped abet the crimes of capitalism, colonialism, and more…

Books & the Arts

/

Elias Rodriques

José Henrique Bortoluci’s What Is Mine tells the story of his country’s laborers, like his father, who built its infrastructure, and in turn its fractious politics.

Books & the Arts

/

Jimin Kang