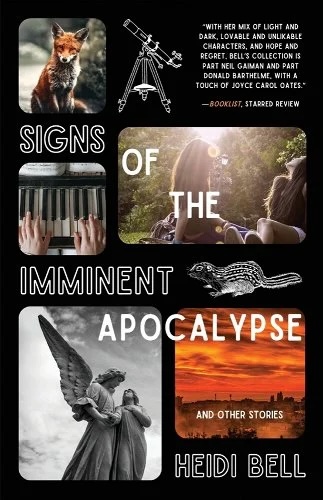

The following is a story from Heidi Bell’s Signs of the Imminent Apocalypse & Other Stories. Bell is an award-winning writer and editor. Her short fiction has appeared in many literary publications, including New England Review, The Good Men Project, Chicago Reader, Southeast Review, and The Seattle Review. She is the recipient of two Illinois Arts Council Fellowships. She resides with her husband in Aurora, IL.

They’re drowning out gophers on Gordon’s hill. Mr. Gordon drags a green hose through the backyard, forcing the grass to bare its yellow roots. He shoves the end into a hole in the ground. I crouch on the shady side of the garage, imagining the gophers and their blind, naked babies paddling as their rooms fill with brown water.

Article continues after advertisement

Leo Gordon comes out the back door, cramming the last of something into his mouth, the sun jackknifing off his white-blond hair, just like his dad’s. I press my cheek against the cool pink siding of their garage, knowing Mr. Gordon’s white Archway truck is inside, surrounded by stacks of cookies in clear plastic packages. My mouth waters just knowing how close they are—the fat, soft lemon-iced, the sugar cookies whose huge granules gather between my fingers. Mrs. Gordon serves them at Bible study, where we read aloud obediently, though some of us will never believe.

From two houses down come the Johns boys and their stepfather, Dick, tromping uphill through the backyards. Billy Johns positions himself at a gopher hole with his shovel, and while he waits for a glimpse of the small sleek head, the striped and freckled back, I pull strings one by one from the hem of my cutoffs. My sister runs past me, doesn’t notice me there at all. She joins the men and boys, squats at another hole, squinting in the sun, her hands twitching inside two Wonder Bread bags. She is determined to have a gopher as a pet.

I do not want to see the gophers washed from their holes, do not want to watch the men and boys kick their limp bodies into the tall weeds that border the back of the long yard, but I can’t seem to leave the shadow of the garage and go home.

Mr. Gordon and Dick stroll over to test the concrete cones they poured around the clothesline poles last weekend. The yard is their place. Inside their houses, they are good only for reading newspapers, for replacing faucet washers and carving meat from bones. Dick kicks a clothesline pole with a black work boot—he wears them even in summer. He examines the pole with small black eyes so mean they can scare your bladder into squeezing tight when he looks at you.

Billy Johns shades his eyes and tracks two teenage girls riding their bikes up the road. His younger brother Marcus kneels at another gopher hole with Leo Gordon. I will go wherever I can to look at Marcus—filthy slit-eyed boy with a mouth the color of Red Delicious. He and Leo are pushing and pulling a stick in and out of the hole, in and out, laughing. Marcus is eleven and banned from our yard for telling my sister and me the joke about a boy named Deeper and his teacher. Now, his and Leo’s giggling attracts Dick’s attention, and he strides over and slaps Marcus across the head. When Marcus flinches away, Dick slaps him again, harder, and Marcus slinks across the yard to stand on the sloping ground behind Billy.

Just then something pops up near Billy’s shoe, and Billy lifts the shovel high to smash it, but on the backswing, he catches the left side of Marcus’s face by mistake. Marcus’s hands fly to his eye, and red appears in the cracks between his fingers as if the sun or a flashlight were shining through. He howls, his lips the rim of a wet hole. My mouth is open, too, my breath coming fast and damp against my hand as I probe the closed lid of one eye, wondering how much pressure the eyeball underneath might withstand before bursting.

Marcus’s yelling voice is unfamiliar, as if other people were talking through him, as if someone were turning the dial on a radio: first he cries, Mama, oh, no, Mama like a little boy, and then he screams, Jesus Christ and Shit. Billy and Dick each grab him under an armpit and hustle him down the hill to his mother’s house, and I am drawn to my feet, as if to follow them.

Instead, I search the hill for gophers. Perhaps this is just the diversion they need to escape, to make new lives for themselves in the tall weeds. Then I see that my sister has trapped one in her hands. Wild teeth rip through the spotted plastic of one of the bread bags and catch the soft web between her thumb and forefinger. Still, she does not let go, holds the gopher with both hands until I knock on the Gordons’ back door and Mrs. Gordon comes out to scold her for touching the dirty animal but still gives us an old metal toolbox to put it in. While Mrs. Gordon washes the gopher bite and sprays it with Bactine, my sister insists she will keep the gopher in her old hamster’s cage. One morning she called me into her room to show me that Buttons was dead by poking the stiff curled body with the eraser-end of a pencil.

My sister carries the gopher home triumphantly in the toolbox, a tissue pinched in the crook of her hand, bright spots of blood seeping through. I follow her down the hill through the afternoon haze that makes the car bumpers and streetlights glitter. I imagine the gophers’ revenge: Marcus Johns cries out as the doctor pushes a needle and thread through the skin around his eye. His mother stands beside him, holding his hand, her face tense with his pain. In the waiting room, Billy Johns sits in a chair and stares at the floor. Out of the corner of his eye, he can see the tips of his stepfather’s black boots. Dick hasn’t said anything yet, and the silence, the waiting, is almost worse than what will come. Tomorrow, on the hill, Mr. Gordon will fill the gopher holes with dirt and plant grass seed, but nothing will ever grow there.

At home, our mother’s hands shake as she searches the phone book for Animal Control. After hanging up the phone, she lights a cigarette and stares at the toolbox, shushing our questions. Finally, she picks up the box and slides it into the freezer. We’re supposed to freeze the gopher, she tells us, and then send it to Madison on Monday for rabies testing.

Rabies. Parents in our neighborhood have been talking about it ever since Beau the golden retriever had to be put to sleep after being bitten by a skunk. At the dinner table, my sister talks nonstop, stirring her SpaghettiOs with her bandaged hand, her spoon scraping and scraping against the blue plastic bowl. Since she can’t have the gopher, she wants a guinea pig, or at least a gerbil. Maybe she already has rabies. Maybe at midnight she will leap from her bed, her teeth grown long and yellow, foam dripping from her mouth as she hovers in the closet connecting our bedrooms. I watch her for warning signs—excessive spit, red eyes, rapidly growing fingernails—as she does a word-search puzzle and watches The Brady Bunch.

There is no dessert, and we have to stay inside after supper. Our mother turns up the television to drown out the sounds of kids outside screaming and running in the thickening dusk, playing Bloody Murder. During commercials, my sister and I think up excuses to go to the kitchen, to open the freezer door and hear the gopher’s nails against the toolbox. Each time, the air in the house seems thinner to me, more difficult to breathe. For hours, the gopher scrabbles back and forth in there. Then it stops.

__________________________________

From “Gopher” from Signs of the Imminent Apocalypse & Other Stories by Heidi Bell. Used with permission of the publisher, Cornerstone Press. This story first appeared in Beloit Fiction Journal. Copyright © 2024 by Heidi Bell.