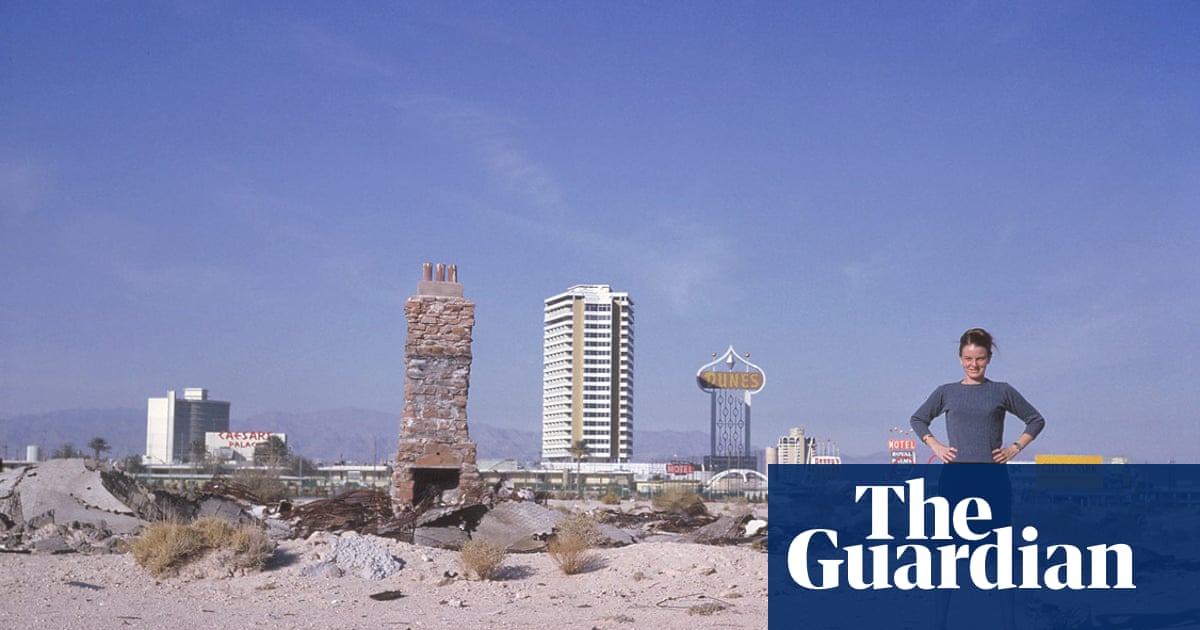

When Denise Scott Brown visited Las Vegas for the first time in the 1960s, she was overwhelmed with emotions. But she wasnât quite sure which ones. âThe first thing I felt was a kind of shiver,â she recalls in a new documentary. âWas it horror or was it pleasure?â She was intoxicated by the frenzy of neon signs that âreach out and hit you as you travel down the highwayâ, and exhilarated by the overload of pure âcommunication without architectureâ. Was there something there, she wondered, that architects could learn from?

Half a century later, we find her back in Vegas, walking around a graveyard of neon signs in a dusty lot with her husband Robert Venturi. Together the duo changed the course of modern architecture, championing everyday popular taste and the âugly ordinaryâ over the rarefied, bleached white world of modernism. They brought back wit, colour and meaning, and embraced messy diversity over the bland homogeneity of so much of the built environment. And Sin City was the cradle of their inspiration â proselytised in their seminal 1972 book, Learning from Las Vegas.

âThis is the equivalent of Michelangeloâs Piazza del Campidoglio in Rome,â says Venturi, as he wanders between the rusting neon signboards propped like architectural antiques in a salvage yard. âAll the holy relics of vulgar commercial America!â He crosses himself and the pair of pensioners let out a mischievous giggle.

It is one of many such charming vignettes captured by their son, Jim Venturi, in the film Stardust, which has its UK premiere at the Barbican next week. More than a decade in the making, the project features numerous commentators who have since died â including critics Brian Sewell, Ada Louise Huxtable and Gavin Stamp, as well as Venturi himself, who died in 2018 â making it a poignant time capsule of voices from beyond the grave. Scott Brown has outlived them all, as feisty as ever at 93.

Stardust is the latest in a niche genre of films about architects made by their children. The punishing profession is clearly something that inspires both a kind of filial awe and morbid curiosity, if youâre forced to grow up immersed in it. Each film seems to ask: âWhy did my parents do this to themselves?â The Venturi documentary follows My Architect â Nathaniel Kahnâs 2003 Oscar-nominated quest to learn about his bigamist father, Louis Khan â and Rem, a 2016 hagiographic feature-length music video about the globetrotting starchitect Rem Koolhaas, made by his son Tomas. Jim Venturi has avoided the schmaltz of the former and the introspection of the latter, preferring to stay behind the camera and let his parents and their peers do the talking. Aided by the judicious writing and editing of co-director Anita Naughton, the film skilfully pieces together archive footage, fly-on-the-wall filming and talking heads to paint a multifaceted picture of this fascinating pair, who emerge as complex and contradictory as the buildings they championed. It is a loving portrait, but it doesnât spare their blushes.

The timing of the London release is fitting, given the brouhaha over the current mutilation of the architectsâ only UK work, the Grade I-listed Sainsbury Wing of the National Gallery, at the hands of another US firm, Selldorf Architects. The film doesnât touch on the controversial plans to smooth over the buildingâs postmodern quirks with a bland blanket of Scandi good taste, but it does reveal how fractious the original design process was. And quite how big the Venturi-Scott Brown ego could be.

âIt was sometimes like dealing with very intelligent children,â says a diplomatic Colin Amery, the late architectural historian who served as an adviser to the project. He recalls having to talk a furious Venturi out of resigning over a disagreement about a window. âHe did say to me, âThey donât seem to realise theyâre dealing with a genius,ââ Amery recalls. âThen he made it worse by saying, âThey wouldnât do this to Shakespeare.ââ

Scott Brown tactfully explains away her husbandâs emotional outbursts by putting them down to his Mediterranean roots. âBob learned to have a Brooks Brothers sheepskin over him,â she says. âBut heâs southern Italian opera underneath.â The National Gallery might be thankful that he didnât get his mobster uncles involved, who feature as a brief, spicy side-note in the movie. (They are described as âthe most feared family in the history of Philadelphiaâ in one archive article â perhaps explaining why a bullet was once shot through the window of the famous house Venturi designed for his mother).

Elsewhere, glorious contradictions abound. The radical duo might have been fans of signs, having championed billboard-smothered âdecorated shedsâ, but they were clearly not happy when signage interfered with their own buildings. One hilarious scene in the film shows the elderly couple back in London to revisit the Sainsbury Wing, only to find a row of advertising banners hung from poles in front of their masterpiece. âAwful!â barks Venturi, his face a picture of horror. âItâs one of the great facades of the goddam 20th century and they put that in front of it? Itâs like putting a billboard in front of [Frank Lloyd Wrightâs] Fallingwater!â Itâs probably a good job he didnât live to see the buildingâs makeover.

For a film about a pair of architects, it is interesting that Stardust doesnât feature their own buildings particularly prominently. Bar the Sainsbury Wing and Venturiâs motherâs house, their work is mostly confined to a series of still images that flash up for a few seconds like postcards. In a way it is apt: the duo were so preoccupied with facades and flatness that a two-dimensional snapshot is perhaps enough. And, as with many architect-theorists, a lot of their own built work never quite lived up to the promise of their writing, and they never achieved great commercial success. They had a tendency to come across as aloof intellectuals, whose uncompromising principles didnât make for easy working relationships. There is palpable bitterness in a section in the film on Philip Johnson, the savvy, opportunistic postmodern architect who essentially took their ideas and made them commercially successful in a way that Bob and Denise never managed.

âPhilip Johnson totally distorted all that we stood for,â Scott Brown says, when asked about the testy term âpostmodernismâ. âHe made it specious and a very big money-making project for architects like him, so that it got a bad reputation.â Johnson is painted as the comedy villain of the piece, and portrayed (not inaccurately) as a misogynist Nazi-lover who had a particular hatred of Denise. As the critic Martin Filler says of Johnson: âYou could put everything he disliked into a computer, and out would pop Denise.â

The spectre of misogyny recurs throughout; one of the filmâs chief successes is correcting the imbalance of credit that has so often been misapplied to the couple. It opens with a scene from a 2006 lecture â with Bob on stage, Denise in the audience â in which Venturi casually remarks that his 1966 opus, Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture, âwas mostly written before I knew Deniseâ. A voice pipes up from the front row: âNo it wasnât!â

It was the story of their entire professional career. Scott Brown became a partner in the firm Venturi and Rauch in 1969, but her name wasnât added until 11 years later. When Venturi was awarded the Pritzker architecture prize in 1991, it was he alone who was named. The accolades piled up, while continually spurning Scott Brown. âBob got an honorary degree from Yale for discovering the popular, everyday environment,â she says at one point. âThe thing that really I introduced and supported is ascribed to him.â She adds ruefully: âMaybe thereâs a shortsightedness in stardom: you canât see enough because youâre blinded by the light that youâre generating.â